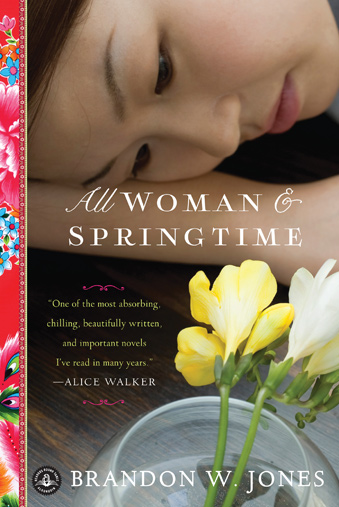

Essay

A Note from the Author

I began writing All Woman and Springtime in early 2009, after a year of listening to a gnawing impulse in the back of my mind saying, "Write! Write! Write!" Like a mantra, it kept chanting, becoming incrementally louder and louder until finally I had no choice but to reply, "Write what? What? What?" It became a call and response, almost a tug-of-war, between my inner drive and my self-doubt: "Write!" "What?" "Write!" "What?" I had been trying to sustain a custom metal art business, making gates and fountains and sculptures of all kinds for a dwindling clientele in the growing tide of the global financial meltdown. Suddenly there was really nothing for me but time and no excuse to continue avoiding the demands of my literary compulsion.

I had been mulling over something that had not been sitting well with me for quite some time, which was the seemingly arbitrary assignation of North Korea to an "Axis of Evil." For all of my many misgivings about such bald judgments, the statement did have the benefit of highlighting for me an uncomfortable gap in my understanding of the world: I knew almost nothing about North Korea, or the history that created the gash across the thirty-eighth parallel. So I began to read, and watch videos, and comb the Internet to take in as much as I possibly could about the region. The more I learned, the more fascinated I became. North Korea is a living Orwellian nightmare, a stark reality so bizarre that it seemingly defies all logic: How could this be happening?

Most of the available media on North Korea (with a few stellar exceptions)—and, relative to information on other nations, the available media is quite limited and full of conjecture—focuses on political issues such as the nuclear threat, the military standoff at the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the chest pounding of Kim Jong-il. Even the ongoing famine is reduced to its political causes and ramifications. The humanity of North Koreans is often lost in the telling of North Korea. So I began my book with a question: How do I find in myself the correct empathy to understand the people in North Korea—people who are simply human, who fall in and out of love, who yearn and ache and strive and succeed and fail just like everyone else, and yet who do it under unimaginable scrutiny, threat, and control? Then I followed it with another question: How can I deliver that empathy to an audience that is, like I was, mostly unaware of the human details north of the DMZ? How do I bring it home?

That is how I met my protagonist, Gi, an orphan girl who condensed out of my growing concern and compassion for the people living within the "Hermit Kingdom." Gi, having lost her sense of self while growing up in dire trauma, comes alive most within the context of her friendship with Il-sun, an irrepressible, mischievous girl at the dawn of womanhood. They are, first and foremost, teenagers, simultaneously reaching for and trying to dodge the lessons of maturity that all young women face. This reaching and dodging places them unwittingly in the hands of human traffickers—a very real problem surfacing in North Korea.

Issues of human exploitation and the regularity with which human beings are bought and sold are a cause of great sadness for me. It is easy to think of slavery as an issue we have overcome, one left to decay in our past, but in reality it is still flourishing, even within our own borders. Though we no longer sanction it with our laws, we sanction it with our collective denial. Human trafficking is a global multibillion-dollar industry, a looming shadow of greed and cruelty. I wanted to inspect this problem from all angles—through the eyes of those who are trafficked, the motivations and justifications of those who traffic, and (though less exposed in my novel) the complicity of those who enable it—and shine a light on it in hopes that spreading greater awareness will erode the ability of those who would perpetrate such abuse.

Though my novel deals with very real places, issues, and situations, much of the journey is metaphoric. For instance, physically crossing the DMZ is unlikely (though there are documented cases), but my characters simply must cross that boundary. The real challenge for them is in crossing it psychologically, transcending the veil of propaganda that is the DMZ lodged within themselves. I see it as a hero story, in which our heroine must eventually face and conquer the darkness within, even after her physical oppressors no longer have a hold on her. To survive she must learn to redefine not only herself but her core beliefs about the world in which she lives.